Problems with Defining Money1

What is money? How does an economic good become a monetary good? What gives money its “moneyness”?

Money is such a familiar part of everyday life that such questions often go unasked. Unasked questions aren’t likely to get answered. It’s no wonder there’s so much confusion on the topic.

This essay is an attempt to address those questions head on and hopefully take some steps towards a clear(er) answer. Before we offer our perspective, let’s examine two popular ways of understanding money today.

Paradigm #1: The Standard Textbook Approach

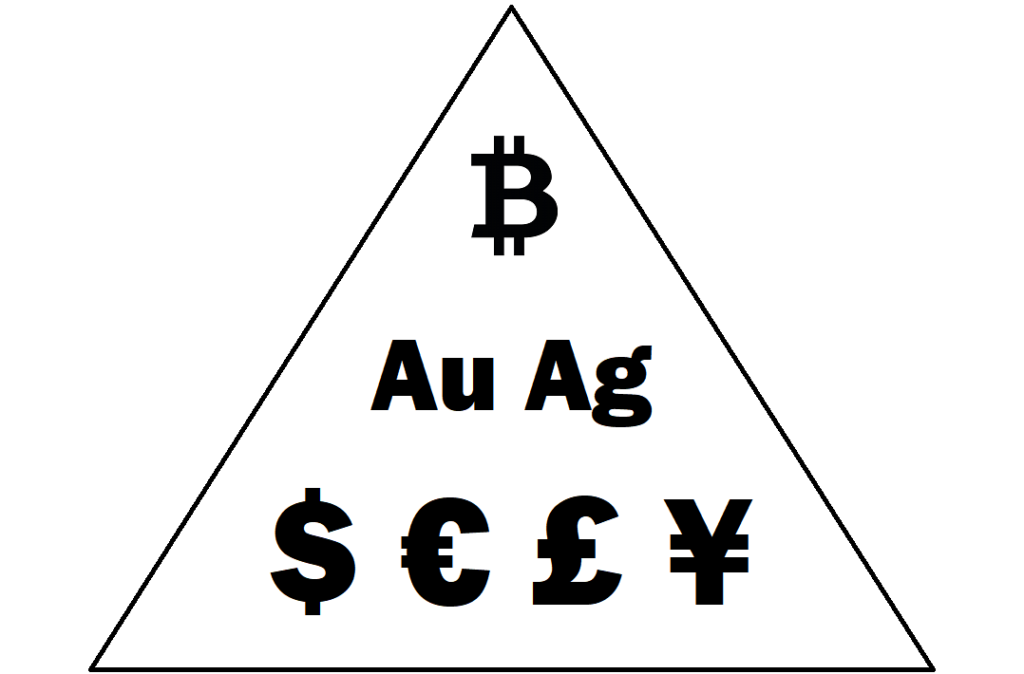

The textbook way to understanding money has been to apply the following three criteria. Money is:

- The commonly accepted medium of exchange

- A Store of Value

- The unit of account

We think this approach is broken, or at the very least, incomplete (later in this essay we will add at least two other fundamental criteria). For starters, these are mostly description, not definition. They tell us about the various functions or uses of money. Money is used as the medium of exchange, used as the unit of account and used as a store of value. Of course, money performs all those functions (and others) beautifully, but we aren’t quite hitting our target. We want to know what money is, not necessarily what it does.

There’s another problem. According to this view, there are several economic goods which may satisfy all these criteria. Short term, high quality credit being is one example. This raises some interesting and hard questions. Is anything that passes this three point test considered money then?2 Are money and credit perfectly interchangeable terms and concepts? Is there something that fundamentally differentiates money from credit? I think there is and we will get to it soon enough. But we promised two popular views first.

Paradigm #2: The Post-Modern Approach

The rapid rise of cryptocurrencies has fueled another view of money we might call the post-modern view. Here, money is whatever anyone or everyone believes money to be. The following quote by Naval Ravikant sums it up well:

“Bitcoin will be a store of value when everyone believes it is. The price is the current probability. Fundamental analysis is impossible.” – @naval

I’ve just about broken my brain trying to think of a clever, witty response to that quote. Alas, all I can come up with is, “No, that’s just not quite right.” (For more on Naval’s thoughts on Bitcoin and money, see Tim Ferriss’s podcast The Quiet Master of Cryptocurrency. or just follow him on twitter at @naval)3

Even if bitcoin were to become the next global money4 it would not be for the reasons Naval describes. Whatever money is, it’s not whatever we want it to be. A person or many persons deciding that X is money, does not make X money. Nor is it simply a matter of having the right number of persons. And finally, the price (which is, irony of ironies, measured in the de facto money) is not a measure of the probability of its becoming a money.5 We need a better analytical framework.

Human beings make decisions in the present based upon expected (or perceived) future utility. Since we live in a world of uncertainty, our perceptions of future utility may turn out to be more or less correct than we originally think. However, utility itself is firmly grounded in real life. Needs and wants are either satisfied or they aren’t i.e. that decision helped or it hurt, more or less, than I originally thought (consciously or subconsciously).

Simply saying “to me this is going to be a store of value” or “to us, this thing will be money,” does not automagically make any of those things money or stores of value. Without skipping too far ahead, it actually happens the other way around. We discover, through a process of trial and error (the “market”) that certain goods are more useful (have greater utility) as money than others. It isn’t a matter of wishing, hoping, dreaming, or deciding that utility into existence. The utility is either there, or it’s not. We find certain things to aid us in achieving our ends. Others do not.

Towards a Better Understanding of Money

Before we can correctly understand money, we need to correctly understand the original problem that money solved and continues to solve today – the double coincidence of wants.

Direct exchange (barter) is costly and inefficient. The shoemaker needs a lot more food, a lot more often than the farmer needs shoes. Half a shoe doesn’t help anyone and food spoils eventually. However, both the farmer and the shoemaker need salt. Indirect exchange for salt elegantly solves this problem for both the farmer and the shoemaker. Instead of directly exchanging shoes for food (infrequently and at a high cost to trade), they indirectly exchange food and shoes for salt. Salt doesn’t spoil and it’s easy to store. They each happily keep any remainder from their exchange in salt as they’re sure to need it later.

Why salt and not something else? That is fundamental question this essay is attempting to answer expressed differently. I think the answer is found in the concept of marketability.6

Marketability refers to how easily and inexpensively one may exchange an economic good for another. The best way to think about marketability is along a spectrum.7 Greater marketability means a lower cost to trade and exchange. Less marketability means a higher cost to trade and exchange. The most marketable good is the good which facilitates the most exchange at the lowest total cost to all parties involved across time8 and all other dimensions. Therefore, when it comes to the question of defining money, marketability provides us with a working answer;

Money is the most marketable economic good.9

In Part II of this essay we will explore the concept of marketability further and look at ways we can measure and compare the marketability of different economic goods in real time. Click here to read Part II: Measuring Marketability

Thank you for reading. I hope you found this article helpful and maybe even enjoyable. I am a student of markets, not a master. If there’s anything in this essay you disagree with, I’d love to hear what and why in the comments below. Thanks again for reading.

Footnotes

- The phrase “Money Functionality” is taken from Hayek’s language in the introduction to Denationalization of Money

- Proponents of this view may point to the use of the definite article “the” instead of the indefinite “a.” It’s not just any good that checks all three boxes, it’s the good, wherein what qualifies the change from “a” money good to “the” money good is typically a function of quantity. That is, whichever good is used the most, or more than all the others, in a defined economy or economic region, is what qualifies that good as the money good. This is all well and good but there are some problems. First, we still have this annoying question about the difference between money and credit. Secondly, the complex, interconnected global economy with its multiple localized units of account amidst global trade with different media of exchange also raises issues. E.g. if the UK trades with the US and uses dollars as the media of exchange but keeps its books in pounds, which is the money? Dollars or Pounds?

- To dispel any doubts, I have nothing but respect and admiration for Naval Ravikant.

- Depending on who you talk to this is either central to the mission of bitcoin, or not.

- The price of an asset is not a good predictor of the possibility of that asset becoming a money. Having worked for almost a decade in the gold industry it is amusing and saddening to see the same arguments employed for bitcoin as for gold a la “Once we hit $_____/btc then we’ve won!” Gold didn’t circulate as money again at $2,000/oz (though many said it would), and Bitcoin didn’t at $20,000/BTC. Yet, there are still plenty of well respected industry leaders who maintain this notion that once a certain price level is hit, the magic will happen and these assets will transform into money. What’s the magic number? We recently heard the number is $64,000/oz for gold. For BTC, it’s over $1million. Don’t hold your breath. I think a better question is – what are the incentives that would cause someone to start circulating (i.e.spending or exchanging) gold, bitcoin or anything else at a certain price level? I think there are good economic reasons (theoretical and historical) which show that a higher price could cause the exact opposite to occur. Higher prices cause assets to go deeper into hoards. They become dearer and dearer to the holder, not less dear. Lastly, one can’t help but note the supreme irony that the measuring stick of value for these supposed up and coming monies is the USD price. This (flawed) approach implicitly and repeatedly affirms the USD as the de facto money even while they use the same breath to herald its eventual demise. “And so blessing and cursing come pouring out of the same mouth. Surely, my brothers and sisters, this is not right!” – James 3:10

- “Liquidity” or saleability may be a substitute for Marketability. Some authors prefer to use the word liquidity. The underlying concept is the same.

- “It also means that, although we assume there is a sharp line of distinction between what is money and what is not–and the law generally tries to make such a distinction–so far as the causal effects of monetary events are concerned, there is no such clear difference. What we find is rather a continuum in which objects of various degrees of liquidity, or with values that can fluctuate independently of each other, shade into each other in the degree to which they function as money. I have always found it useful to explain to students that it has been rather a misfortune that we describe money by a noun, and that it would be much more helpful for the explanation of monetary phenomenon if ‘money’ were an adjective describing a property which different things could possess to varying degrees. (Machlup for this reason speaks occasionally of moneyness and ‘near-moneyness’)” Hayek, The Denationalization of Money Pg. 56

- For example, for the dimension of time we might say the Dollar is the best short term money available, but suffers over longer dimensions of time against other monies, such as gold. And whereas gold has proven a better money over longer time periods, it weakens when used as money in shorter time frames

- Acknowledgement to Carl Menger for this definition. Cited from On the Origins of Money, an absolute must for anyone who is interested in monetary theory.